SEEING RED IN TOMBS, TEMPLES & PALACES

- Sep 24, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 25, 2025

With the theme of our recent study days at Bolton Museum ‘Ancient Egypt’s Art and Artists’, the primary colours used by the ancient craftsmen each has their own story to tell. And no more so than in the case of red, or ‘desher’.

Now according to ‘the Sherlock Holmes of ancient Egypt’, archaeological chemist Alfred Lucas, “the only red pigment known in ancient Egypt until very late” was red ochre. And while he did concede that red plant-based dyes were also used by c.1350 BC, the dominant source of this powerful colour was indeed ochre, the iron oxide mineral Fe₂O₃ often referred to as ‘haematite’ from the Greek word αἷμα (haima) meaning ‘blood’.

Certainly the colour’s direct association with the blood that sustains life yet shed in death has always made a powerful impact on the human mind. Ever present in art since the very beginning, the world’s earliest-known drawing dating back some 73,000 years to South Africa features lines of red ochre, also used to outline human hands in the caves of southern France around 30,000 years ago.

In the same region some 10,000 years later, the Lascaux Cave Paintings of the Dordogne - discovered exactly 85 years ago this month - were created by those living in these caves using on-site grinding stones to crush the same ochre, mixing it with water to apply to their caves’ limestone interiors where images of wild cattle include four huge aurochs up to 17 feet across. With obvious parallels with Egypt’s oldest art of similar date dubbed “a ‘Lascaux along the Nile’” (Lascaux on the Nile - World Archaeology) by the late great archaeologist Dirk Huyge, multiple stampeding aurochs discovered high in the cliffs of Qurta in southern Egypt were ideally placed, the sun’s daily journey still bringing them to gradual life in the play between light and shadow.

Despite intensive weathering, Dirk interpreted the repeated cut marks across the necks of some of these Qurta creatures as evidence of ‘hunting magic’, in which such ‘art’ was meant to perform a function (7 minutes into https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZU2Roq-emxw). So it’s tempting to imagine that red ochre pigment may once have been applied here too, as throughout the rest of Egypt’s ancient history when the potency of images could be further enhanced by the choice of production materials. And especially so in the case of red, which for the Egyptians not only symbolised blood but the sun as it rose and set in reddening skies, powdered red ochre has also been found in some of Egypt’s earliest known burials from the 5th millennium BC, sprinkled over bodies interred in foetal position, with the suggestion that the grave acted as a womb from which the deceased might then be reborn into the next world like the sun appears each dawn.

And it’s the same powdered red ochre pigment identified on the walls of Egypt’s earliest painted tomb at the southern site of Hierakonpolis c.3500 BC, where images of large boats were interspersed by human figures hunting wild animals, fighting each other and executing prisoners, all painted with red ochre before selected areas were overpainted in black manganese. This then became the way all such images were created in Egypt for the next three and a half millennia, the ancient draughtsmen initially using red ochre to outline the planned scenes whose typical linear layout was soon achieved by following a grid system, bringing balance and order to the random chaos of nature, and again set out in the same red paint to maintain standard proportions (below).

Likewise the way in which red ochre paint was used to guide the chisels of the stonemasons tunnelling down into solid limestone to create rock-cut tombs, as we ourselves encountered in the Valley of the Kings royal cemetery. For here in the highest – and we believe oldest - tomb in the valley, designated KV.39, blobs of red paint had been applied to the tops of the walls in a regular sequence all along the main passageway (below), likely spaced out using a cubit measure such as the wooden example owned by tomb-builders’ foreman Kha (demonstrated 34 minutes into https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pSClqMN1hXM). And with Stephen’s onsite analytical work within KV.39 revealing the multiple masons’ marks had been manufactured c.1500 BC by blending crushed ochre with plant oil and imported conifer resin to create a bright yet durable red paint, the source of this special mineral lay very close by, in the nearby ‘Valley of Colours’ within which countless coloured patches of both red and yellow ochre can still be found within Luxor’s special landscape (below right).

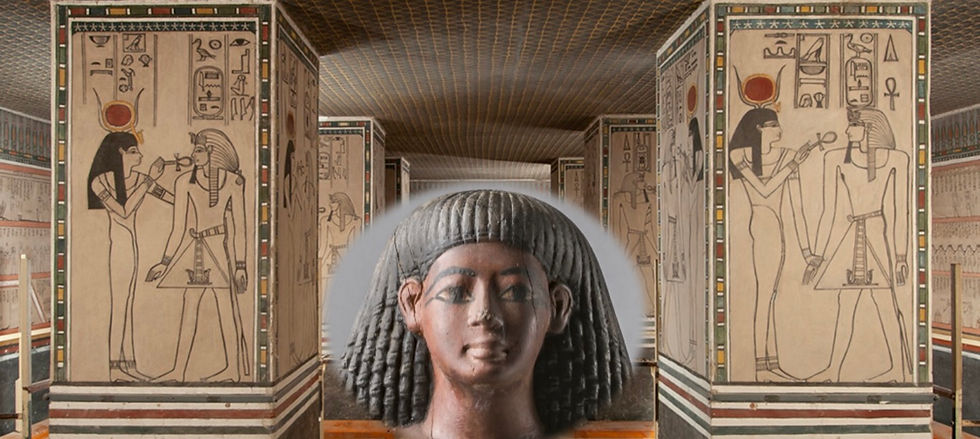

Yet KV.39, like all the earliest royal tombs here, was otherwise completely undecorated, and it was only by c.1450 BC that the valley’s royal tombs began to be painted. Beginning in the tomb of Tuthmosis III (KV.34), the ancient artists used a limited colour palette of predominantly black and red (below) to create the Egyptian version of the Afterlife, the so-called Amduat or ‘What is in the Underworld’. Portraying Tuthmosis’ soul journeying through the nightly darkness in the company of the gods, to be reborn each dawn with the rising sun, red was used to great effect when highlighting both the sun disc and key sections of accompanying text, and while the tomb itself is currently closed to the public (but with special access for tours including https://www.theculturalexperience.com/tours/ancient-egypt/), the exact replica of this very tomb within Bolton Museum can also be viewed online here https://discover.matterport.com/space/AJk3xWK8H7t thanks to our great friends at FrontRowLive.

So its amazing to think that this very tomb, the first in the Valley to be decorated, is likely the place in which the aforementioned Kha began his long career. Then moving on to work for Tuthmosis’ successor Amenhotep II, whose own tomb KV.35 emphasises goddess Hathor and the striking red sun disc atop her crown (below), the king she protects awarded Kha his second cubit as a mark of royal favour. But this cubit was covered in gold, with an inscription referring to Kha’s work further north at Hermopolis on another royal building, most likely within Hermopolis’ temple complex.

And just like Egypt’s tombs, its temples, all too often regarded as a sea of beige, were similarly embellished both inside and out with colours almost shocking in their intensity (44 minutes into https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pSClqMN1hXM), as revealed by a recent cleaning programme which removed multiple centuries of dust, soot and wind-blown sand to staggering effect (below).

It’s also a similar story with domestic interiors, from surviving wall décor inside the small houses of the tomb-builders’ village Deir el-Medina with their own splashes of red to the royal palaces, the bull-leaping scenes created by the Minoan Greek artists commissioned by Tuthmosis III at his Delta residence at Tell el-Dab'a dominated by their crimson background.

Then at Amarna inside the ‘King’s House’, archaeologist Flinders Petrie discovered the famous image of two small princesses (below), once part of a much larger wall scene showing their parents Nefertiti and Akhenaten all sitting comfortably with at least five of their children, and possibly Akhenaten’s son Tutankhamun on a further fragment of the scene. With its red background representing the palace’s soft furnishings, these red-dyed floor cushions with the same blue and yellow pattern as the red bolsters padding the sills of the palace’s Window of Appearance faithfully replicate surviving examples of these very same textiles (below, as highlighted in my 2003 book ‘Search for Nefertiti’ p.295, plate 9 https://www.immortalegypt.co.uk/store).

And while the ubiquitous red ochre was often used to colour such fabrics, the plant dye Rubia tinctorum aka ‘madder’ was also introduced into Egypt during this same 18th dynasty timeframe, as reflected in some of the red textiles found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, including at least one example of the so-called Amarna sash. For this long linen belt worn by the royals was made of the most highly prized textile of all, the bright red linen referred to as ‘ins’ or ‘insy’, as offered to the gods who were even portrayed wearing red clothing, from Osiris as ‘Lord of Red Linen’ to his sister-wife Isis and other key goddesses Hathor and Sekhmet, Mut and Bastet, aka ‘Ladies of Bright Red Linen’.

The colour was particularly appropriate for the combined goddess Hathor-Sekhmet, daughter of the sun god as well as his protector. His enemies were warned that “she appears against you, she devours you, she punishes you” as she waded through their blood which soaked into her linen robes, one famous legend revealing how Sekhmet almost destroyed the entire human race. In fact the other gods were only able to stop her with a decoy of red alcohol, variously interpreted as red wine or beer mixed with red ochre which, as intended, she mistook for human blood and lapped up, soon so drunk she fell asleep and changed back into the placid albeit deeply hungover Hathor (see https://www.immortalegypt.co.uk/post/wine-in-ancient-egypt-i).

And with red linen so closely associated with these powerful daughters of the sun through whom all were reborn, it’s unsurprising that the mummified elite were sometimes wrapped in shrouds of this same red linen bringing together the reviving powers of Hathor-Sekhmet. From the queens Nefertari, Henuttawy and Nestanebetisheru to our old friend Merit, wife of Kha (below), our analysis revealed that Merit’s outer wrappings had been further enhanced with a most unexpected embalming mixture made up of the fragrant if costly Pistacia resin mixed with oil from the red-hued tilapia fish (below) sacred to Hathor (see: https://www.immortalegypt.co.uk/post/testing-merit-s-crowning-glory & Shedding New Light on the 18th Dynasty Mummies of the Royal Architect Kha and His Spouse Merit | PLOS One).

Invisible to the naked eye and serving no preservative purpose, this fish oil must therefore have been chosen for its protective powers, much like ingredients listed in magical spells: from red linen wrappings and fragrant resins to fish blood, red ochre paint and the juice of a ‘fiery red poppy’, Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch noted that “the juice of such a poppy probably would not look red, but was regarded as containing the essence of redness”, much like the tilapia fish in fact.

Yet in the same way the sun brought life but could also destroy it, red was also used in spells to punish enemies, the enemies of Egypt themselves regarded as ‘red things’ and perfectly reflected in the duality of Egypt’s landscape, 95% of which was known as the ‘Red Land’ or ‘Deshret’. As the origin of our very word desert, signifying a hostile environment rather than the colour of Egypt’s distinctly yellow sand, the vast expanse of barren Deshret was in sharp contrast to the fertile Black Land or ‘Kemet’, the 5% strip of dark silt deposited each year by the annual Nile flood which brought life to an otherwise desert environment. For Egypt has always been a land of two parts, ‘Red Land: Black Land’, combining to represent the contrast between life and death visible even from space (below).

But even beyond such natural divisions running east to west, the Egyptians used red to demarcate political affiliations too, with red representing the north and white the south in the original version of the War of the Roses’ colour scheme. North and South even had their own crowns, red and white, each emblematic of the two halves of Egypt which when worn together signified a kingdom united. This resulting double crown of red and white was known as the pschent, from the original term ‘pa-sekhemty’ meaning ‘the Two Powerful Ones’ in reference to the two heraldic goddesses protecting each region, the great white vulture Nekhbet of the south and the fiery cobra goddess Wadjet, whose sinuous form appeared at the brow of each monarch to embody the fierce red heat of the sun she too represented.

All part of the wonderful world of ancient Egyptian regalia in which the placement of a certain jewel, plait or pleat can reveal so much, the way such features were combined to such powerful effect is a constant source of fascination. Take these two images of queens Nefertiti and Nefertari (below) for example, both featuring these same protective images: the innovative combo of crown and earrings worn by Nefertari, with the Nekhbet vulture at her brow and its wings framing her face beneath a red modius crown while Wadjet the cobra appears as a golden earring, the same goddess’s serpentine form (albeit now missing her head) still guarding the equally beautiful features of Nefertiti.

And check out the two women’s subtle use of cosmetics too, from their characteristic black kohl eyeliner to that same crushed red ochre, used on Egyptian faces since at least c.4000 BC and apparently still used in beauty products due to its ‘ready availability, stability and non-toxicity’. Giving a rosy glow to their royal cheeks, so too Nefertiti’s red lip colour so striking it inspired a range of lipsticks from Christian Louboutin (above right), while as early as the 1920s and 30s Chabrawichi of Cairo were producing Nefertiti’s red rouge and perfume in their own distinctive packaging which now forms an important part of the Egyptomania Museum’s collection (below left).

Even some three thousand years later, it’s possible to pinpoint the delicious scent of such great royal women, our lab-based research allowing us to recreate ‘signature fragrances’ using ancient favourites including red-coloured myrrh oil. And with Stephen recreating this as part of our recent ‘Queens of Egypt’ study days in Bolton, it allows us to make contact with all-things red and powerful on so many sensory levels.

Jo’s first book ‘Oils and Perfumes of Ancient’ was published by British Museum Press back in 1998 https://www.amazon.co.uk/Perfumes-Ancient-Egypt-Joann-Fletcher/dp/0714127035, and as she and Stephen continue to develop its themes her next talk looks at the way the ancient Egyptians sourced and mined gold and precious stones at: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/mining-in-ancient-egypt-and-beyond-with-professor-joann-fletcher-tickets-1527376667729

Comments